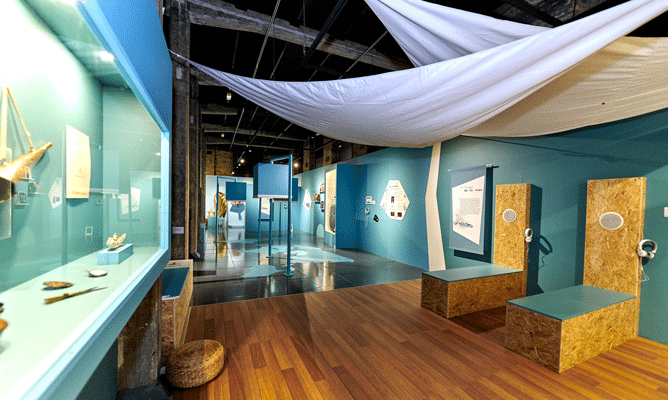

"Listen", in its former use, means "to give ear to". This exhibition is a true invitation to give ear to the sea, its living wonders, neighbours, travelers and admirers. Welcome to a sea of sounds and music!

'"D'Eau Ré Mi" is a fully translated exhibition !

We successively switch from a noisy urban environment through some confused hubbubs to well-balanced musical atmospheres and popping sounds of our mobile phone all day long... but do we still pay attention?

"Listen", in its former use, means "to give ear to".

This exhibition is a true invitation to give ear to the sea, its living wonders, neighbours, travelers and admirers. Welcome to a sea of sounds and music!

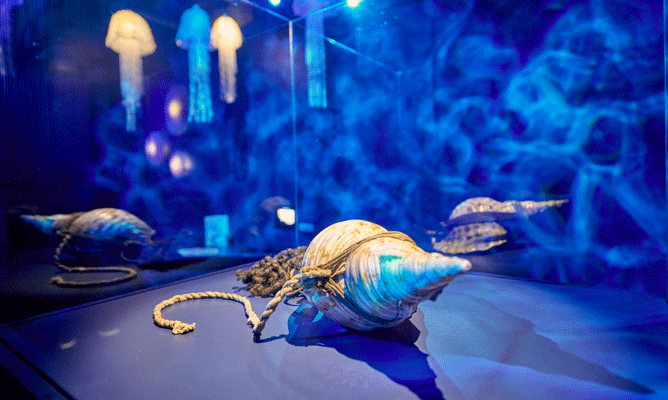

The sea is a musical scenery that swings along the rhythm of the waves. Our beating hearts follow the motion of the sea: sometimes it thrills us, sometimes it soothes us. Still, the sea produces richer sounds from the abysses to the surface that no human ear can perceive. Marine species we long thought were mute, are now giving their unrevealed babblings out to the biologists' microphones. Shrimps snap and fish vocalize: some pop at a pistol rate, others hum and hoot just like birds do. Whales and manatees produce a modulated song so similar to human voice that it probably gave birth to the mith of sirens and their charming songs that lured sailors to the deep sea.

The rise of monotheistic religions left this musical and aquatic pantheon behind, leaving only chimeras and hellish creatures into people's mind. Despite time and all efforts to convert people to new dogmas, old beliefs travelled through the ages and mingled with new religions among the inshore populations. To this very day, many societies are still currying favour with the sea by means of songs, incantations or offerings addressed to divine figures who link men to invisible forces such as deities, saints or even benevolent spirits.

They charm sailors by their spellbinding song and lead them to reefs to better drown and devour them.

In the 12th century, mermaids (half-woman, half-fish) superseded sirens (half-woman, half-bird) once and for all. Artists usually depicted mermaids holding a golden comb and a mirror, their hair hanging down their naked shoulders and breasts.

In iconography and ancient texts, mermaids holding musical instruments embody winds and cardinal points or even omens of the tidal wave preceding the Apocalypse.

In West-Africa, Brazil, the West Indies and the Caribbean, folks celebrate a water deity who is usually portrayed as a mermaid or the Virgin Mary.

In many French Coast cities, including Dunkirk, sailors praise the Virgin Mary by carrying her effigy through the streets of their city during processions. During the ceremony, a priest blesses the sea and tosses a wreath of flowers into the ocean, in the memory of lost souls.

Mamy Wata is the very mix of various religious symbols.

Her appearance may differ in some countries: she either has Hindu features or is portrayed as a dark skin woman with black hair, brandishing a snake. Her fish tail, which reminds us of a mermaid, is a vision that has been spread by Portuguese sailors trading slaves across Africa. Mamy Wata also finds its roots in another divine figure named Yemoja.

For the Yorùbá people of Togo, Benin, Nigeria and Congo, Yemoja is the Mother Goddess of the Ocean. Her figure evokes freshwater and sea water and symbolizes fertility. She is the one who made a well-known present to men: seashells that would convey the voice of the universe. She is part of many religions that were brought to the Americas by African slaves. She has many shapes and many names: Manman'dlo in Guadeloupe, Erzulie in Haiti, Yemanja in Brazil.

The musical instruments travel around the world and evolve at other musical repertoires and traditions touch.

Antic worlds and faraway lands echo through contemporary music. Music follows trade routes, travels through countries and pays no heed to frontiers and social cleavages. It carries within itself the seeds of the social relationships that are made of unique stories, appropriations, subjugations, cultural diversity and unpredictable mixes. As such, music is a universal language.

For centuries, it was a way to communicate and orally transmit stories and culture from a generation to another, which forged each community identity and bound it to a territory.

As the colonial economy, travel, and overseas trade started to develop, the local traditional repertoires moved with the newly arrived passengers. Waltz, mazurka and quadrille were dances brought along with the Great Atlantic Migration. Calypso, salsa, biguine, merengue, zouk, soul, blues, rock, jazz would not exist today if the African culture and its music had not exported itself and interbred with the Indian and European ones... The West Indies, the Caribbean and the Americas thus unveiled a large musical palette which creativity shines on the rest of the world.

Until the very last century, sea roused most people's fear and fascination. It was considered as the homeplace of seamen who lived on the fringes of a respectable society. Changing mentalities took time. In the 19th century though, sea made a dramatic entrance into the classical music art and overwhelms all arts. Composers sought to capture its variations, just like the ones of a shifting landscape whose infinite and changing nature is the mirror of the human soul.

On board, music not only gives daily work its tempo but also entertains seamen on Sundays. It soothes their temper and melancholy, it glorifies their heroes or taunts worthless shipowners and mediocre captains. On land, the invention of leisure brings back the long gone pleasure of singing songs to city dwellers, on summer trips to the beach.

At the beginning of the 20th century, windjammer ships are still sailing some of the trade routes such as the Cape Horn one. Crowded and solid crews are needed to sail four or five-masted ships through the violent Southern Ocean storms that constitutes a meteorological barrier on their way to Chile's coasts to load nitrate up. Seamen usually sing along together to help find strength when handling physical activities such as weighing the anchor, steering the vessel (to direct and change its course) or when hoisting the sails .

On British ships, the shantyman leads the duties by a piquant and cheerful chant (shanty) that is mostly improvised. The soloist always starts by a call that is responded to by the rest of the sailors. Most of the time, a capella songs are inspired by the ones heard on land.

At the end of the Age of Sail, work chants almost disappeared. Fortunately, some lovers of the maritime cultural heritage and musicians started collecting and recording these songs.

Harbours are places where people from all backgrounds, inland folks or seafarers, meet. As such, harbour cities are prone to musical creativity. The blending of worldwide and local music illustrating specific social situations or cultural phenomena gives birth to brand new music styles. Thus, the Milonga music and the Argentinian tango that were originally considered as the music of marginalized people, ended up being the artistic symbol of Buenos Aires as the fado is to Lisbon. As for the port of Piraeus, it gives Athens the image of a rebel city, incarnated by the rebetiko music. Everywhere on the docks and in ship holds, popular or rebellion songs accompany hard labour.

Every harbour identity is shaped by its own accents, sound colour and musicality.

Your turn! You are now Neptune!

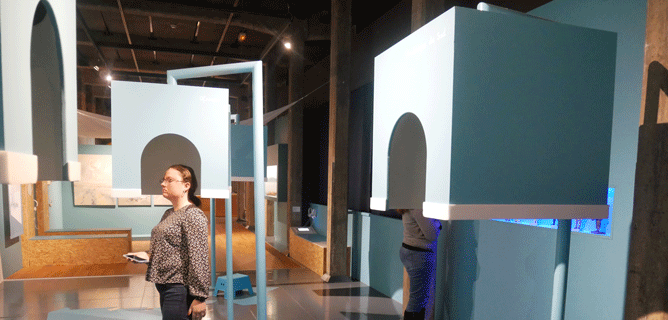

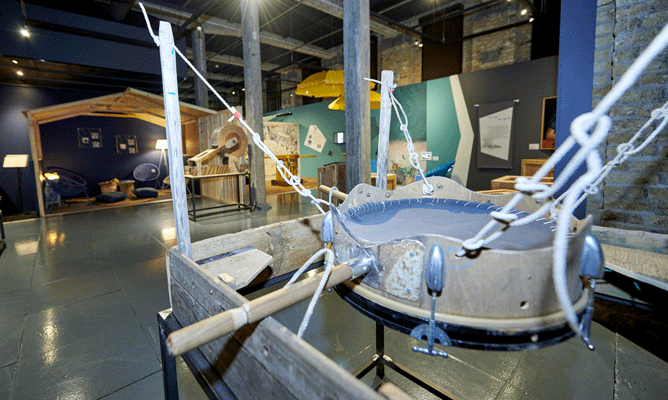

The sea workshop has been designed and built by Frédéric Le Junter, a local artist and musician born in Dunkirk and who is fascinated by harbour sounds.

Since 1984, this brilliant multifaceted artist has been creating experimental sound machines out of recycled materials he sets up and moves from festivals to exhibitions.

These mechanical engines originate from the machines we use to produce theatre sound effects.